[ad_1]

By Heidi Wilder, Special Investigations Manager & Tammy Yang, Blockchain Researcher

Part 1: What are Bridges? Bridge Basics, Facts, and Stats

Illicit actors are often attracted to the newest forms of technology, and bridges are unfortunately no exception to that rule. Illicit actors are defined as individuals or groups conducting illicit activity, such as scams, thefts, or other illegal activity, on the blockchain. In the previous section of this blogpost, we covered the Wormhole and Ronin bridge exploits.

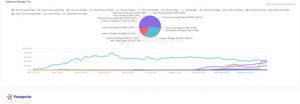

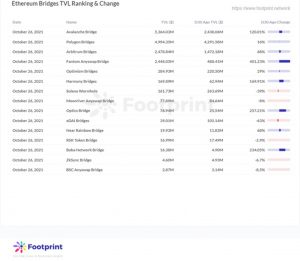

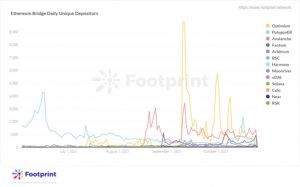

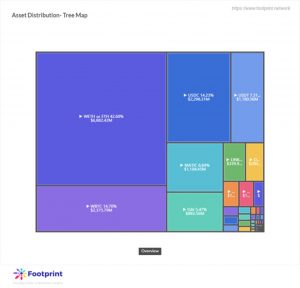

Analyzing the use of Ethereum bridges by illicit actors in January 2021 through April 2022, we find that Ronin, Wormhole, followed by Polygon and Anyswap have the most volume flowing through them.

To date, Ronin bridge’s exploit that took place in late March is the largest hack in the DeFi space, totalling more than $540 million in funds stolen (as of the day of the bridging of funds). We discussed this exploit in more detail in our previous blockpost. Unsurprisingly, this hack makes up the largest illicit volume with the Ronin bridge.

Wormhole’s Ethereum-Solana bridge was attacked in February 2022, leading to a loss of over $250m.

Polygon’s bridge was primarily abused by Polynetwork’s exploiter (although funds were returned), the bZx hackers, and the AFK System rug pull. The bZx hackers appear to have literally gone back and forth between chains to decide which ones were best to consolidate funds. Ethereum won in the end.

Anyswap BSC bridge was primarily used as a bridge by the Bunny Finance flash loan attackers, Squid Game rug pull and Vee Finance hackers.

Why would illicit actors want to bother bridging at all?

Illicit actors’ reasons for bridging funds between networks are both similar and different compared to the general population of bridge users. Possible reasons include:

- Consolidation. Combining funds through bridging makes them easier to handle and to generally then launder onwards.

- Obfuscation. Bridging over funds to other networks adds another layer of complexity to tracing funds on-chain. Tracing funds that travel through a bridge requires tracing capability on both networks and linking them through the bridge.

- Faster and cheaper transactions and to use assets that are not native to the network. Bringing over funds to other faster and cheaper networks can aid illicit actors in transferring their funds more rapidly at a lower cost. The added ability to access assets that aren’t native to the network allow both licit and illicit actors to gain price exposure to a non native asset, while also enjoying the benefits of the other network.

- To access a broader selection of dApps. As blockchain monitoring has become increasingly popular, so has scrutiny of illicit activity:

a) Instead of immediately cashing out, some illicit actors will choose to bridge over funds and then yield farm with them for a period of time, which has the benefit of passing time and earning interest on their proceeds.

b) Alternatively, illicit actors will also leverage certain DeFi protocols that help break the chain in order to obfuscate the true source of funds.

But how are illicit actors employing these methods in practice? What happens after someone has bridged over funds to another chain? Can you track through a bridge to the other side?

Because of the transparency of the blockchain and of many bridge protocols, we can trace through various bridges to identify the ultimate destination of funds.

Below are some recent examples of how illicit actors are employing bridges and how we can trace through bridges to identify the ultimate destination of funds.

Consolidation and obfuscation — as seen with an NFT phishing scheme

NFT phishing scams are nothing new, but the scale at which NFT phishing scams are occurring on social media is rampant. In this particular case, we observed several Murakami Flower phishing scams, among other popular impending NFT releases.

In this case, we observed that several of these scams bundled together their ill gotten ETH in a novel way.

Instead of pooling their ETH together on Ethereum, they bridged over the funds to the Secret Network, which was likely an attempt to obfuscate the source and destination of funds.

Although they may have bridged over funds to the Secret Network, they continued to bridge over to the same address over and over again. Consolidating funds from various phishing schemes allowed them to better get a grasp on their funds.

Accessing a broader set of dApps — an example of using bridges to then yield farm with ill gotten gains with the Squid Game rug pull

In November 2021, the Squid Game token rug pulled. Although the token was launched on Binance Smart Chain (BSC), funds were bridged over to Ethereum. While this was likely for obfuscation purposes, it was also to gain access to Ethereum-based dApps.

In particular, once the attackers bridged over funds to Ethereum, they opted for two yield farming strategies, which allowed them to earn interest on their ill gotten gains.

The first, was to swap funds to USDT and to supply liquidity to the ETH/USDT Uniswap pool (one of the deepest pools on Uniswap). The second was to take the ETH and to lend it on Compound.

While the attackers have begun to cash out, they have not only waited out the heat but have also made some interest while doing so.

Accessing a broader set of dApps — an example of using a bridge to access DeFi protocols to break the chain of traceability with a malware operation

A malware and ransomware operation primarily sourced funds from victims in Bitcoin over the years. However, in the latter half of 2021, the operation began to bridge over funds to ETH using Ren.

This allowed the attackers to mint renBTC. Using a particular protocol, Curve.Fi Adapter, the operators were able to immediately swap the newly minted renBTC for WBTC. Both renBTC and WBTC are BTC-backed tokens on the Ethereum blockchain. It’s important to note that the attackers specifically wanted WBTC though, which they could then deposit to Compound.

Compound is a DeFi protocol that allows users to earn interest on their deposits. When a user deposits funds into Compound, such as ETH, they are provided with cETH or Compound ETH in return, which can be exchanged through Compound for the original ETH amount deposited plus interest earned. Alternatively, users can also use the cETH as collateral to then borrow other tokens.

And that’s exactly what the malware operations did. They used cBTC as collateral to then borrow stablecoins from Compound, particularly USDT and DAI. And with those stablecoins they then cashed out at various exchanges.

The idea here is that the malware operators were attempting to obfuscate the true source of their funds and to make it seem like they received funds directly from Compound.

What can we do about this?

Because of how public, traceable and permanent the blockchain is, we can leverage it to not only identify illicit actors bridging funds across blockchains but also to stop them. The primary mechanism for this is blockchain analytics.

Here are some steps we can take as an industry to combat illicit actors’ bridging of funds:

- Work with blockchain intelligence providers to identify cross-chain transactional flows to quickly identify when illicit funds have hopped from one network to another;

- Block illicit actors addresses’ on both sides of a bridge;

- Monitor inputs and outputs of protocols that are heavily abused by illicit actors who bridge over funds.

Using these and other tools we aim to preserve the integrity of the ecosystem while also encouraging innovative concepts, like bridges, to expand the crypto economy.

[ad_2]

Source link